14 Spells (to save your life)

Updated: 2023/11/07

- Photography

- Emma Summerton

- Interview

- Olivia Gagan

Olivia Gagan: Tell me about the genesis of 14 Spells (to save your life). How, why, when did these images came about?

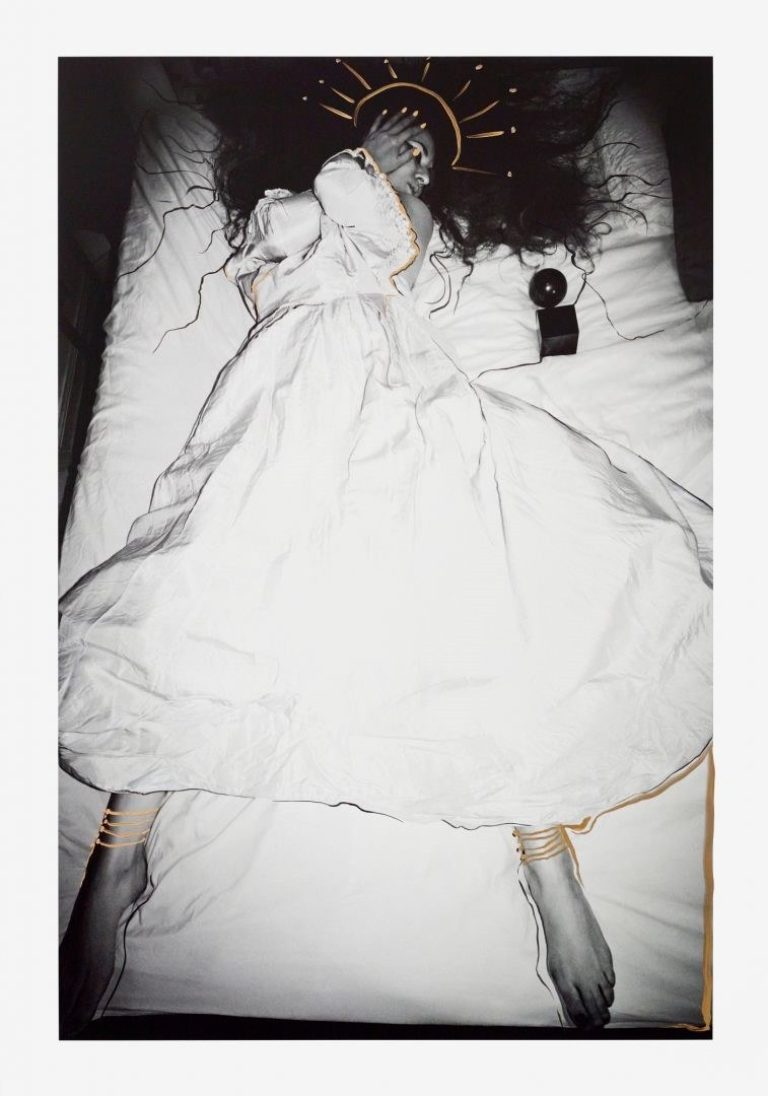

Emma Summerton: It's a fair question, because they're quite removed from what anyone expected from a new show. I had done a lot of self-exploration – digging and inquiries into in utero memory, when I started thinking about what these self-portraits were going to be like. I started thinking about pregnancy, and myself as a baby. They're kind of self-portraits as a baby in utero. I'd been working with a therapist in relation to my art and work, and she talked about your work becoming your baby.

This reminded me of a conversation I had with one of my mentors, really early on when I first left art school. She said to me, “your work will always save you.” And that idea really stuck with me through my career. It's something that's always got me through. It's a mantra that has always got me through difficult times or self-doubt. It’s [the idea] of just putting everything into it. I also wanted to bring in elements of nature.

It's about creation, and self-creation. Yourself as a baby, and then the different stages of who you are. When I was shooting, Me, Myself and Her, it represents these different parts of yourself. It's the rebellious teenager, and then you're morphing into what you want to be. And then Her is the person that I never became. I guess it's about expectations of what women are meant to do in their life as well, you know? Who we're meant to be.

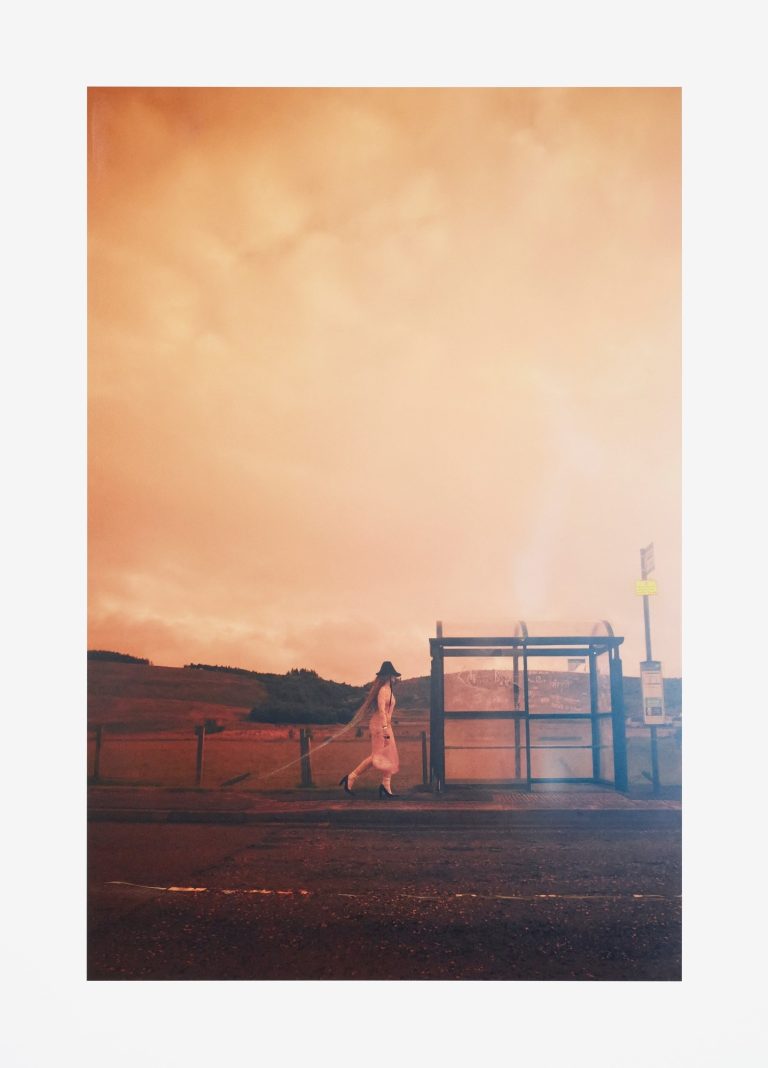

The images seem to play with archetypes as well. The mother, the lover, the bride, the witch. Would it be fair to say that you are exploring different roles for women through different ages of their life as well? You span the entire lifetime of a woman through this exhibition – from being in utero to the Leaving image at the bus stop. I mean, you could interpret the idea of leaving in a whole wealth of ways.

Definitely. Leaving for me was about leaving where I grew up. And then the painted strings [in the images] are like the things that pull you back. Your mother, your family. It’s hard to leave, but you have to because you have to go and become who you are. I've been spending a lot of time talking with a friend of mine, Donna. She has a 16-year-old daughter and I was at her birth. Me and Donna have these conversations about how in those teenage years you do become like a monster against your parents – because it's the only way you're gonna cut the cord, and go and be an adult and have your own life.

In the Caul

Leaving

You've got to individuate and separate yourself. Be like, ‘I'm not you’. At some point you have to cut that cord.

Yeah. ‘You don't know who I am!’

It's interesting what you were saying at the outset, about exploring early memories of yourself as a baby or in utero. It feels like birth and motherhood are quite potent themes in these images.

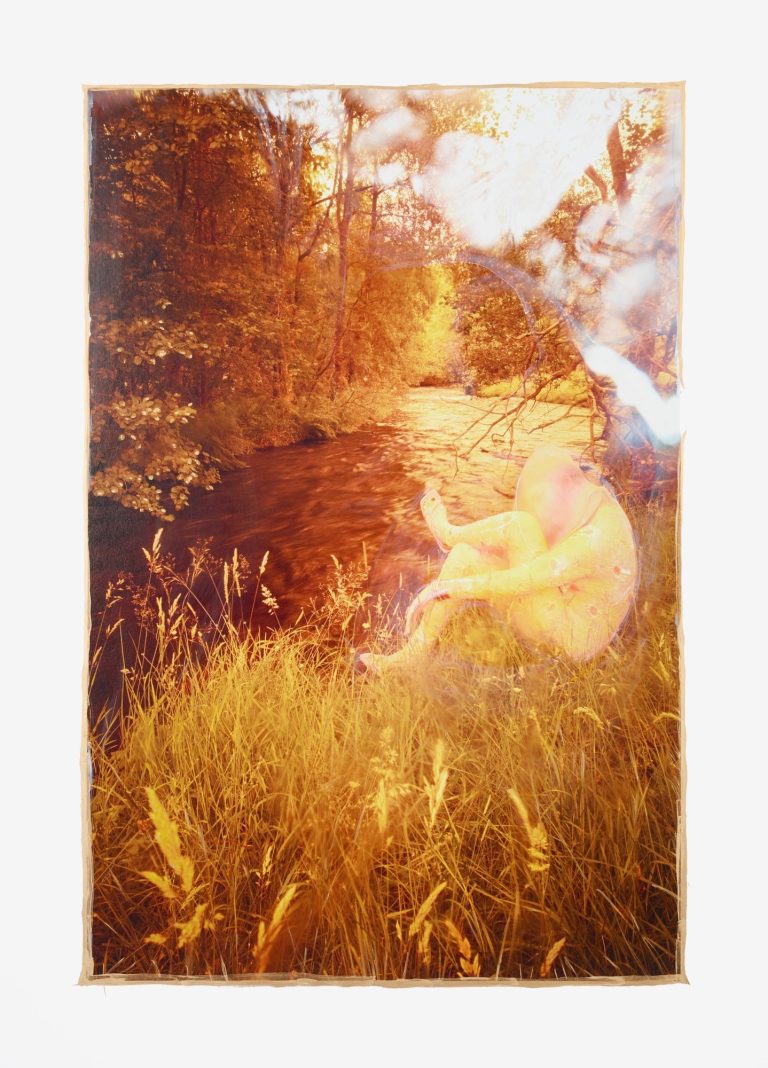

Yes. And birthing new work. Working in fashion, you dip in and out of things very quickly, but I wanted to immerse myself in this. There was a real pull towards nature and the earth, and going back to some sort of primal way of making work where you are taken over by your environment, and not controlling it as much as I'm used to in fashion. So I created a sense of freedom, of ‘whatever's gonna happen is gonna happen’. I really wanted to open things up to mistakes, if that's what you want to call them. And not having to be too serious about it. Really getting into a sense of playing.

You can sense that playfulness and movement. What was the process for making the images? Were you working largely alone?

When I do self-portraits, I am pretty much alone, or there's one other person with me, depending on what my life situation is. When I did the self-portraits back in the early 2000s, I was in this love affair with a photographer. We'd go on trips together, but this time, I went to Scotland for two weeks and the first week I was on my own.

I asked a very old friend of mine of 30 years, Belinda, if she would come for the second week. I was going to be out in the wilderness by rivers and waterfalls, and I started to think, ‘what if I tumble down a hill and break my leg? No one's gonna hear me. There's some spots where there's no phone reception’. So I called her and said, “okay, this is weird, but do you want to come?”

The thing is, I'm not a performative person. I don't enjoy being watched while I do things like this. But because I know her so well, it didn't feel like that. We ended up in fits of laughter most days, because the flip side of doing the images is kind of hilarious. Hiking up a hill in a latex bodysuit with a baby bump in your backpack! <laughs>. There wasn't a structure. It was just, let’s wake up in the morning and feel what the day wants. Some days the weather was four seasons in a day, so there was a need to be really fluid about it.

Pre & In Utero

I think self-portraiture in any kind of medium can be a powerful way for women to self-actualize and to explore elements of themselves. Is there anything that helps you, or anything you think is important when you're trying to take a self-portrait?

The thing for me is to drop my guard down. There's a paragraph in Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes, which I really related to when I was at art school:

“In front of the lens, I am at the same time: the one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, the one the photographer thinks I am, and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art…I invariably suffer from a sensation of inauthenticity, sometimes of imposture… / the Photograph (the one I intend) represents that very subtle moment when, to tell the truth, I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object…”

…it’s about the forces that happen when someone is being photographed. There’s what the photographer wants, what the person expects the photographer wants, and the inauthenticity that they feel being photographed. So it's kind of like these forces come together, that Barthes describes as almost like a death. It's almost like a death of the ego – because to really give something to a picture, you have to let go of all these ideas or expectations of what you are expecting of yourself, and of what someone else is expecting.

So it’s about dropping your guard and maybe letting go of the idea of control, because you can't control all the various elements that will inevitably come into a photo.

Yeah. And having a bit of a sense of humour about yourself. I find that helps me anyway.

Where did fashion and clothing come into this series, conceptually? There's some amazing pieces – the prosthetic bump, a latex piece.

I thought about it a lot. I didn't take too many things with me [to Scotland]. Most of it was pulled from my wardrobe – I've collected lots of different things over the years. Shoes, hats, gloves, weird things from flea markets. I had the latex bodysuit made by someone in London, made to measure, because I wanted it to be like a second skin. The prosthetic bump I ordered online, from this place that makes different sized bumps. I was scared to open it for the first month that it was here. <laughs> It became a box in my apartment where I kind of forgot what was in it. Then I almost forgot to take it with me when I was leaving to go to Scotland. It was kind of hilarious because it's like this idea of looking after the baby, of taking care of your work. It's like, God, am I one of those people that would leave the baby on the roof of the car? <laughs> I really approached it with a lot of trepidation. It was very interesting.

Lalo Tree

Can you tell me about the drawings you did on top of the images? The threads that are overlaid over the photos? To my mind, they're reminiscent of ropes or threads. I thought maybe they were referring to family ties.

They’re pastel, watercolours, ink. I think they are threads joining the figure into the landscape – this idea of other energy that is around us and in the air, that we can't see. A friend introduced me to the woman who runs the Spiritualist Society in London. I was already planning to paint on the images, but I saw all these pictures there, where people who [called] themselves photographic mediums would paint ectoplasm on to photos.

So it was also about the idea of other worlds, other dimensions coming into reality. Photography has become this thing where you can create anything. Especially now with AI, it's just like, who knows what's real. But I loved the idea of hand work, not Photoshop, you know.

These images feel like the opposite of AI. They have work that's literally hand-painted onto the image. The collection's title is really beautiful and evocative, too – spells to save your life. Is that something you hope for? That people that see these images find something that is helpful, soothing, or comforting to them? Or is that more a message to yourself?

The title came before I made the work, which happens a lot with me. Making the images was about not saving my life, but [making] spells to understand your life, to understand how you ended up where you are and, and to make peace with your journey and with your choices.

People’s reactions have been surprising, and beautiful sometimes. There was one woman that came up to me at the exhibition opening and said, “It's such brave work. You're so brave”. And I was like, “I don't understand what you mean” <laughs>. For her, the images were about being a woman of a certain age that chose not to have children. I think partially it is for me. I'm 53 so you know, those choices were made. It really resonated with her and made her feel quite emotional.

I think it's nice for people to find their own meaning. My art theory teacher when I was at art school absolutely hated me, because I just hated talking about [the meaning of my work]. I'm like, ‘just tell me what you feel’. And he'd be saying, ‘what did you want to convey?’ I’d reply, ‘it's none of your business’ <laughs>. I think once it's done, the meaning is out of your hands, in a way.

Me, Myself & Her

14 Spells (to save your life) shows until 19 November 2023 at Christophe Guye Galerie, Zurich, Switzerland.

Related Articles

Cat Power

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews