Glow Like Moons

Published: 2023/09/09

Updated: 2023/09/27

Higgie was a long-time critic and editor at Frieze magazine before recently ending her tenure to become a full-time writer. Her departure from the magazine has proved prolific. The Mirror and the Palette, a book on self-portraiture was published in 2021. 'The Other Side' was published in 2023. Another book is in development.

Higgie chronicles with an illuminance that welds her readers to the page. 'The Other Side' concentrates primarily on women artists creating between the eighteen hundreds and contemporary times. The historical context of spiritual interest rooted in the role of mysticism in art is highlighted throughout the text—including the First Nations origin stories, Greek myths, and paintings' relationship to alchemical process.

Weaving narratives together, Higgie highlights the Fox sisters, who played a central role in the Spiritualist movement. Their influence, directly and indirectly, impacted the trajectory of artists such as Georgina Houghton, Emma Kunz, Hilma af Klimt, Pamela Colman Smith, and Leonora Carrington. These women’s names are only a small sampling of the robust history documented. Higgie is an astute scholar with a vivid capacity of linking social connections between creatives.

'The Other Side' is lush and atmospheric, offering readers an understanding of spiritualism's legacy within art practice. The women written about are vanguards who pushed the boundaries of their eras. These are women who used their subconscious energy to take a brush in hand and unlock the beauty of unconstrained, unconventional artmaking.

Poet and therapist Katie Ebbitt interviews Jennifer Higgie about her relationship to preternaturalism, scholarly study, art criticism, the pandemic, and what it means to take a leap of faith when it comes to one's own creativity.

Katie Ebbitt: 'The Other Side' has an intuitive reaching when it comes to the artists you detail. I am curious about your process of choosing the individuals you write about.

Jennifer Higgie: It was an interesting process. It was a bit like being a detective on some level and on another level, it was to do with a type of therapeutic process in that I was finishing a job that I had been doing for two decades. I was exhausted. I was looking for a re-enchantment. I wanted to make clear that it was in no way an encyclopedic take on this subject. It was more the artists that I stumbled upon in my research who moved me, who touched me, whose work I responded to.

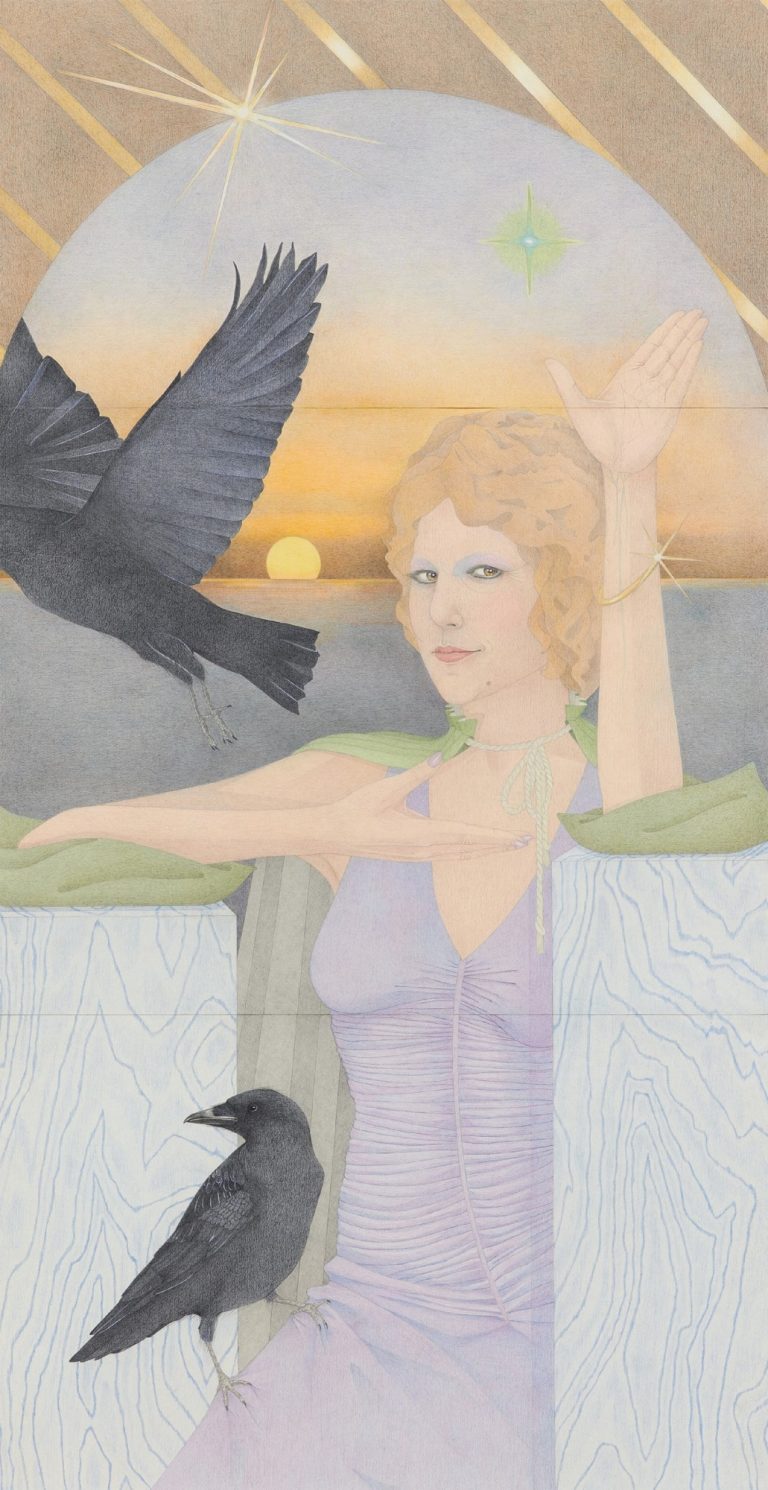

I was interested in looking at the origins of the modernist spiritualist movement. People like the Fox sisters were really important in the movement. While the sisters weren’t artists, they were so influential on artists like Georgiana Houghton. The fact that she met Kate Fox was interesting. I write about Hilma af Klimt as being my gateway drug to this world. It was my friend Donna who did the cover drawing for the book. She is one of my closest friends. She is Australian but is here in London. She introduced me to Hilma af Klimt over ten years ago. And I was like, “who is this?” Very few people knew of her then.

I went to the Moderna Museum in Stockholm and that’s when I saw that exhibition that completely blew my mind and completely rocked the foundations of the art history I had been taught. During the writing of the book, The Gallery of Everything in London, curator James Brett, contacted me and said I think you will really like this artist Janet Sobell and would you write something for me about her. I had no idea who she was. I discovered her and her impact on Jackson Pollack.

My friend Simon Grant curated the Georgiana Houghton show at the Courtauld Institute of Art in 2018. Then I saw her work . There was an amazing exhibition at the London College of Psychic Studies that I went to, just before lockdown. And that blew my mind. I had long conversations with Vivienne Roberts at the London College of Psychic Studies, and she taught me so much about people I had never heard of. It was an organic process of discovery.

The exhibition of Australian aboriginal artists that I saw in Canberra at the National of Museum of Australia. I looked into the Songlines, and the Seven Sisters, and how I was living close to Seven Sisters road, there are all these funny connections. And my love of Greece and reading Circe by Madeline Miller. There were so many threads to this story.

You wrote that for so many of the women artists that you were documenting that art wasn’t a profession or vocation, but a calling. I wonder if you relate to that as a writer and art historian—that intuitive understanding of what is institutionally given isn’t necessary the line of discourse you want to follow.

I have nothing but admiration for a whole host of professional artists who are very much working within the contemporary scene. I don’t mean on any level to criticise their approach. But when I was at art school, we muddled through, and then put on exhibitions in these empty spaces. And we didn’t expect to make money or become part of a commercial system. I think that was due to being a young artist in Melbourne in the 90s.

Now when I teach at art schools, every young artist will give me their business card. It is a very different environment. These young artists have websites and social media. They are able to market themselves. And I understand that, if you don’t you are doomed to a life of waitressing, which is what I did for a long time. It’s not that I am criticising that they are very professional, but rather that it’s refreshing to come across artists where it’s the only thing they could have possibly done. They did it even when scorn was poured on top of them, and they had no political agency. At a time when women are banned from art schools, academies and apprentices, but still, they did it.

I became fascinated by artists to whom it would have been impossible to not be artists. Even though they had everything thrown against them. It’s something I explored in my previous book, the Mirror and the Palette. I find it extremely moving when you come across artists who make art against all odds. It’s like being an eternal optimist. Somehow there is a reason for me doing this. I don’t know why. But I will continue doing it. Even if no one looks at it and I am mocked. I will keep doing it.

I kept thinking who does create without thinking of creation as an otherworldly process?

That’s a great question. There are a lot of writers who don’t think of themselves as particularly spiritual or of it being a spiritual practice. One of the things I wanted to make clear with the book is that I use the word spiritual in a very broad way, because it can be manifested in so many ways. It can be artists who are communicating with spirits or a religious practice or an honouring of your dreams or it can be following your intuition. I don’t think there are any artists, even those who are avowed atheists who don’t have some connection. They still trust things like intuition and feeling and how they react to a certain color or a certain shape or are interested in art making itself as an alchemical process. Literally it’s art changing one thing into another thing, whether it be a medium or an idea. And it becomes a language that can’t be anything other than itself.

I think it would be impossible to be a creative person and not to trust the unknowing of what might be the end result of this strange act of creation. In that sense I wouldn’t call all artists spiritual but I feel that all artists to a certain extent deal with mystery.

'The Other Side' helped me to ground myself in a creative lineage I didn’t realise I was a part of.

Women have been censored for millennia and that’s what women battle with. I am working on an idea for my next book and I can feel the nay-saying voice in my head this—this isn’t valid or this isn’t right. I would love to reach a point where I have total unconstrained freedom with my imagination and unconscious. It’s a very difficult state to get to. Feeling this way in the twenty-first century, imagine what it was like in the ninetieth or eighteenth century for women. Where they were not considered worthy of a voice. And then you see what these women create—its phenomenal.

And extraordinarily brave.

Coat ERDEM, earrings and cuff 886 THE ROYAL MINT.

People ask why wasn’t Hilma af Klimt didn’t put her work in the mainstream like Kandinsky did. Why did these women have their secret circles, their women’s groups? And it seems so obvious to me, they were tired of being ridiculed. Even though Hilma af Klimt went to art school and she did really well at art school it was in a very conventional framework. I don’t think women at that time were encouraged to be radical, to be radical thinkers about the world.

Hilma seemed to understand how radical she was at the time. This awareness maybe led her to protect herself against misunderstanding of her work by not displaying it until after her death.

Absolutely. You look at the big artists who made a name for themselves in the twentieth century and they are brilliant artists. I don’t doubt their talent for a second, but they tend to be big characters, too. Picasso is an example. He is a great artist but a fairly terrible man. He wasn’t shy about trusting his instincts and selling himself to the public. There is a correlation between massive self-confidence and financial success as an artist, or critical success as an artist. I love thinking about Georgiana Houghton in London. How in 1870 she decided to put on an exhibition of her pictures. I would love to time travel and visit her in that gallery. It’s the 1870s. She’s a respectable middle-aged, middle-class woman sitting in a gallery on New Bond Street with these pictures which must have looked like a spaceship in the middle of Piccadilly. And she sits there for three months looking after these pictures and talking to anyone who came in. She found the bravery to do that because she was advised to do it by a very mysterious man who we don’t know much about. Also, her spirit guides encouraged her to have this exhibition. Of course, she was mocked, but she also had some pretty good reviews as well with some newspapers going, this is really fascintating. She wrote an autobiography so we can get some sort of insight into what she was feeling and thinking at that time. She says the most interested people were other artists who came to talk to her about her extraordinary pictures. She’s like the cosmic Jackson Pollock sitting in this gallery in 1870 with a dagger in her hair. I love the dagger in her hair.

Such an incredibly beautiful and bizarre portrait. The tenacity she had.

Such tenacity. There was something about Georgiana was very secure in her community. She was in deep mourning. She'd lost many members of her family. Then she goes to this seance that a neighbor is putting on, she learns things in that seance that no one else could have known about her family. So, she becomes a believer, and then she finds a really happy community. When you read her autobiography, she's really cheerful, you know? But the extent of what she was experiencing I could have spent a lot more pages just describing what happened to her. It was quite trippy and hallucinogenic, but she believed it. Absolutely. And, it resulted in these amazing pictures. But she had a solid community of support, and I think that was really important. She wasn't isolated.

Community is central to the creation for the women you write about. I was also struck by how many dead sisters you mentioned—and how this introduced your artists to spiritualism.

I hadn't thought about that actually, but it's very true. Yeah. Hilma’s sister died, Georgiana’s sister died, and there were other dead sisters as well. But I mean, of course, we can't imagine the amount of what people had to cope with—with the amount of mortality in every family. And, you know, we think that they would've been more used to it, but you never get used to someone dying. I'm reading actually at the moment; I'd never read it before, Charlotte Bronte's Violette. It’s a strange book and I haven't read Charlotte Bronte for years. And it's reminded me of what these three girls were like, these Bronte girls all dying in their twenties or thirties and in this remote parsonage spinning these worlds out of nothing. It's extraordinary. And I'm sure that a lot of that came from grief as well, and the sense of the fragility of life. They all probably knew that they would die young.

You mention in the text that because of the First and Second World Wars, people were seeking something outside of the destructiveness given to them—and how this need for something else impacted art creation.

I think grief is a great creative prompt. You know that you can see that through literature, through art. I also think one of the really important things was, especially the First World War, really led to a great mistrust in what people thought should be taken for granted. If you've got governments that condone the slaughter of ten, twenty-million young men on the battlefields of Flanders, well, why should we trust everything else they say? It was the First World War.

And, you know, of course, immediately afterwards, that's when women start getting the vote as well. War has a terrible power, and also seemed to have challenged mindsets that were carved in stone. The outpouring of different ways of examining the world through art and literature immediately post the First World War is absolutely extraordinary. That combined with mass industrialisation; I also found it really fascinating how many scientists were really interested in spiritualism—from Thomas Edison, who tries to design a telephone that you can ring the dead with. And he's serious. And Marie Curie and Einstein—to be at that level of scientific thought is an act of extraordinary creativity because basically you're dealing with possibility. And that's why in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, there was such a crossover between science and art, because artists and scientists are all looking for new ways of understanding the world and communicating with it. And so, if an x-ray can suddenly look inside someone's body, or a telegram can send a thought across an ocean, well, why can't we communicate with the dead? Maybe what we understand of time is crude. From what I gather, scientists are still saying, physicists are still saying that our understanding of time is crude.

How can you possibly do anything scientific without just this extreme imagination? You're grasping at something which is completely outside of what we know.

Exactly. Yeah. Imagine being able to dream up a light bulb.

Yeah.

It’s extraordinary. Or a telephone or a satellite.

I play that game with myself of trying to think of things that don't exist. And to be honest with you, I've never been very successful.

No, no. I totally know what you mean. I think that if things had been left to me, there wouldn't be wheels or anything.

In 'The Other Side' you write about your relationship to self and food and art practice and botany over the pandemic. The inwardness that you were discovering over the course of lockdown—this intense focus on the world around you and stopping after a long time of transience. Can you talk about that?

It was sort of a perfect storm of things, really. Leaving Frieze magazine after twenty years and going to Australia, and then getting caught up in the bushfires, those terrible bushfires at the end of 2019. I've never seen such devastation in my life, and it was horrific. I can't explain how horrific it was.

And then coming back to London and the pandemic beginning. I repurposed my bushfire mask into my pandemic mask. I totally acknowledge how horrendous it was for so many people. I realised though that I needed stillness. I'm very lucky in that I have a small garden. And I realised that I'd never spent much time in my garden. And I'd lived here for a few years, and I'd never really explored it. Just being out in the garden, and I was making these little watercolors too. I was too shy to mention this in the book. But I just go into the garden and take my watercolors out there and just pick one leaf that was lying on the ground and observe it all day. And I just make a little watercolor looking at it really closely, not to show anyone, not to have an exhibition, not to make anything groundbreaking, but just to look at a leaf.

And it was so incredibly satisfying and sort of nourishing to stop and observe a leaf in my garden. And then there was that wonderful exhibition at Camden Art Centre called The Botanical Mind, which was an amazing exhibition. All these things were converging. I was listening to Hildegard of Bingen, and as I mentioned in the book, my mother had brought me Hildegard of Bingen to play at art school.. And there was some Hildegard of Bingen, small illuminated manuscripts in that exhibition or online. I started thinking about weaving and thinking about meeting Sheila Hicks in Paris and Lenore Tawney’s exhibition, and then the Weavers of the central deserts of Australia, who are so extraordinary. And then thinking about the weavers in Greek myth. It was a really amazing time of sort of introspection. It was the first time that I'd been able to sort of let my mind wander where it would.

Coat and shoes VALENTINO, earrings 886 THE ROYAL MINT.

'The Other Side: A Journey into Women, Art & the Spiritual World' by Jennifer Higgie

Drowsing in the heat, I kept thinking about an exhibition that I had visited on a rainy afternoon in July 2021, just as lockdown momentarily lifted in London. Titled ‘Strange Things Among Us’, it was staged at the College of Psychic Studies, founded in 1884 and housed in a grand Victorian townhouse in South Kensington.

Four floors of rooms were filled with spirit photography, psychic drawings and paintings, Ouija boards, planchettes and more. Faces emerged from the ether; flowers bloomed from chalky ground; minds clicked like cameras. The exhibition was enthralling, not least in the way it cast a new light on a famously censorious era: the nineteenth century. The curator, Vivienne Roberts, showed me around. She explained that by focusing on various preternatural energies – auras, souls, visions, spirits, ghosts – she wanted to explore how ‘the strange things among us’ have the power not to terrify but ‘to evoke awe and wonder in our lives’. In one of the strangest years in recent times, I drank it up.

To trust in art is to trust in mystery. The suggestion that no serious artist would attempt to communicate with, or about, the dead or other realms falls apart with the most perfunctory scrutiny. Across the globe, the spirit world has shaped culture for millennia. In the West, the Bible was the source of most pre-modern art – and it’s full of magic, the supernatural and non-human agents. Where would the Renaissance be without its saints, angels and devils, its visions of humans manipulated by powers beyond their comprehension? Or Ancient Greece without its gods and goddesses, who shape shifted at the drop of a hat? Or, for that matter, the many riches of First Nations art? But then art itself is a form of alchemy – the transformation of one thing (an idea, a material) into another. It is in its nature to be allusive rather than literal, to deal in association, symbol, and encryption, to honour intuition and imagination over reason – all of this chimes with much magical practice. It’s as unconcerned as a prophet with accuracy.

Physicists tell us that our reading of time is crude, but artists have always known this; they constantly mine the past even as they’re imagining possible futures. How can change – be it new machines or new ideas – be visualised if it can’t first be imagined? And who would ever assume that imaginations run along straight lines? Most artists are, in some shape or form, time-travellers and ghost-whisperers. They have myriad ways of accessing the dead: via the tangible proof of their thinking – books or paintings or music, say – or through more esoteric means: mediumship, in tuition, ritual, dreams, call it what you will. Although numerous nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists created their pictures via spirit communication, the more I discovered about them, the less I cared about the veracity of their claims about connecting with the dead. The creative act is often mystifying; to pin it down and dissect it is possibly the least interesting – and possibly most futile – thing you can do with it.

I’m fascinated by the ways in which arcane beliefs have influenced the course of art over the past 150 years or so and, in particular, the drawings, paintings and sculptures made by women. For too long, these works were seen either as fascinating curios or sidelined or omitted from Western art history, despite the clear and documented reality of their existence. Even in art, reason, order, and ambition were considered to be masculine traits; men were active and intellectual, whereas women were assumed to be passive, fragile and emotional. Many of the explorations and innovations of artists who happened to be women were seen as eccentric – although in the early days of modernism they often drank from the same spiritual well as their male contemporaries, many of whom were lauded. However, it’s not only the omission of female artists from art history that is significant: in the nineteenth century, some of them were also vocal about women’s rights. It’s hard not to see a correlation between their criticism of patriarchal power structures and their absence from the male-shaped canon. Sometimes, the best way to shut someone up is to ignore them.

It’s worth reiterating that finding inspiration from the deep

past does not mean avoiding the present. The falsehoods we have been told about women’s contributions to the artistic life, for one, dissolve in the face of historical fact. Despite being taught for too long that culture was, in the main, shaped by men, there are well documented accounts of mythic and historic women who exerted their influence across all spheres. But of course, it’s only very recently that women’s contribution to art (and everything else) has been acknowledged. Gender exclusion, including that of queer, trans or non-binary artists, is just one of numerous omissions. First Nations artists, artists of colour, those who weren’t professionally trained or who are differently abled, all were – and in many cases, still are – sidelined or ignored. A true story of art should reflect the fact that humans make art, and that what it means to be human is infinitely variable. What is clear is that at a time when women didn’t have the vote and were barred, in the main, from training as professional artists – and had to acquiesce to masculine authority on just about everything – Spiritualism allowed not only a creative and personal freedom but a sense of community free of male control and criticism.

Today, the words ‘spiritual’ and ‘soul’ have become kitsch approximations of immateriality that imply a vague yet sincere search for something inexpressible and communicated from a higher plane. But still the question lingers: What is a spirit? God’s prophetic voice? Someone who has died but refuses to rest? An ancestor? An immaterial energy? A sense? An agent of good or evil? A belief in a god or goddess is an equally complicated business; even the meaning of the word ‘god’ is open-ended. Is it an energy or a being? Male, female or gender nonconforming? A human in spirit form or something or someone beyond our comprehension? Each artist who has grappled with these questions has come up with a different answer.

From the book 'The Other Side: A Journey into Women, Art & the Spiritual World' by Jennifer Higgie, Copyright © 2023 by Jennifer Higgie. Reprinted courtesy of W & N, an imprint of The Orion Publishing Group.

Related Articles

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews