The Isolated Figure

Updated: 2021/07/05

- Interview

- Katy Hessel

- Artwork

- Sarah Ball

KATY HESSEL: I think it’s an interesting time to speak to people about their work because I think we potentially could look back on this to see what it was like being in the middle of it all.

SARAH BALL: Yeah, I think ‘they’re’ planning an exhibition of works, aren’t they, that people are making and things.

Oh, are they? Amazing.

I think I saw something. I mean, it’s interesting that people are making films and music videos and all sort of things, aren’t they? Everybody’s been creative.

Yeah, it is. Okay, so the first question I wanted to ask you, obviously you know I’m a huge fan of your work—when did you become interested in figurative painting specifically?

Oh gosh. I think I’ve been on quite a journey, really. I started making big abstract works, but they were based on figurative observation of something, and they’d be huge paintings but of tiny minuscule details and they were from wildlife things. I then started looking at what the actual creatures were or parts of the creatures, so photography came into the work that way. And then I just became obsessed with collecting old photographs, basically. So I worked with archival stuff and Victorian work, just all sorts of things, circus things, all sorts of things. This is a long time ago, and all of that fed into the work and it sort of became part of the work, the photograph itself became part of it, and then the journey progressed so that it was the figure that was in photographs that became the work itself. And then that just opened up so much. I was interested in how figures and faces are read and it just all came from that really.

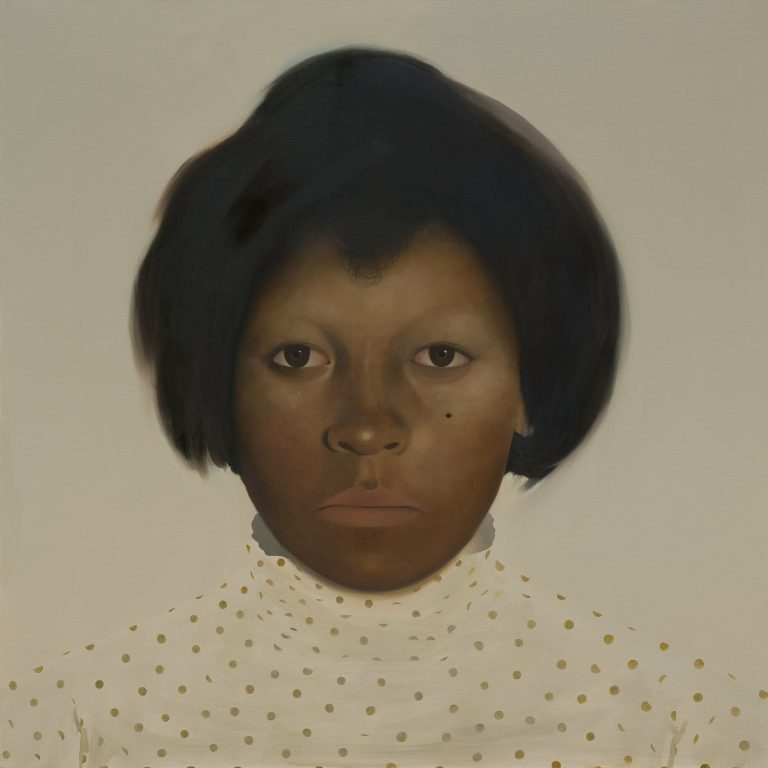

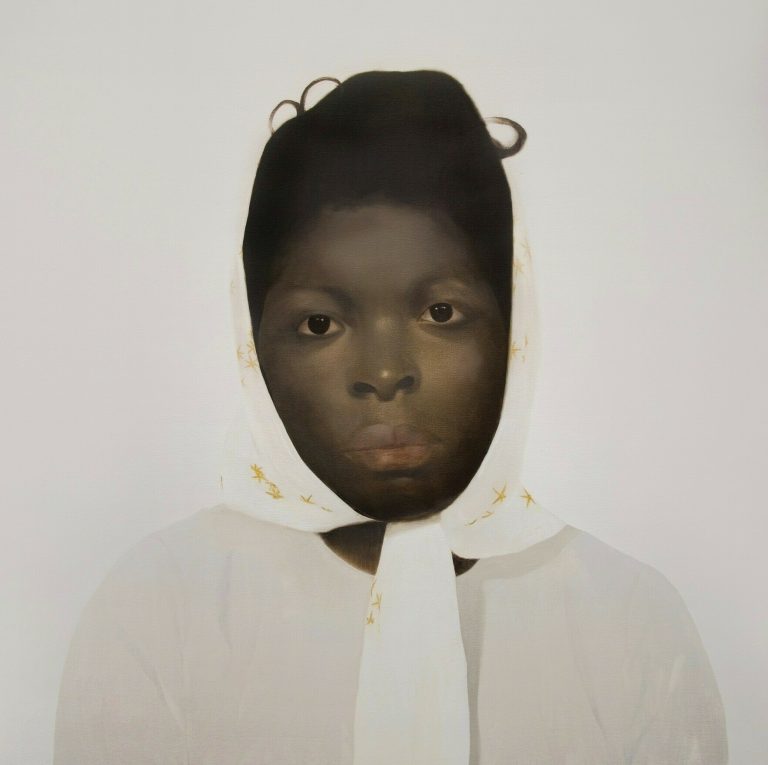

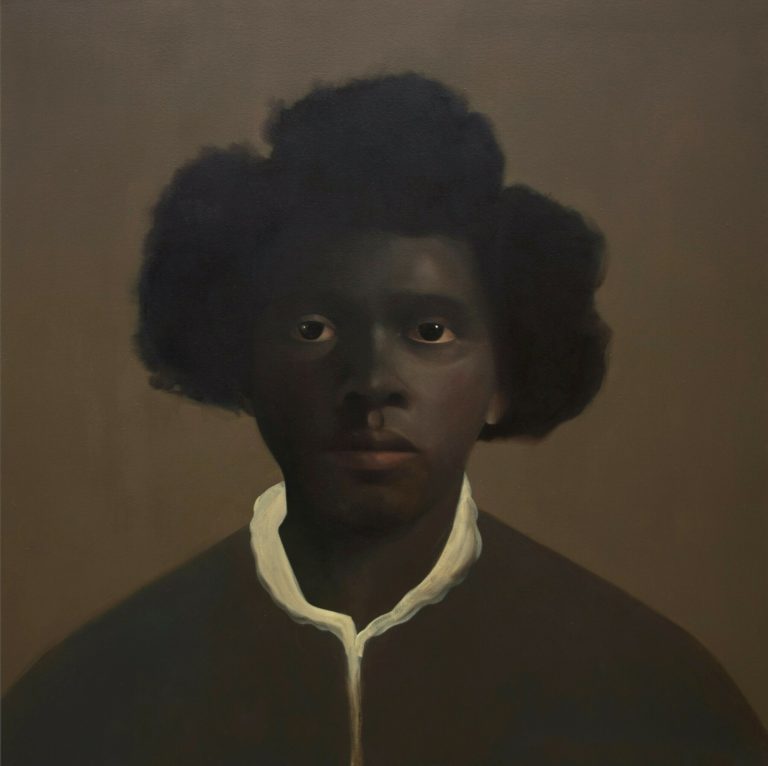

I think it’s so interesting because your work, for me, it’s so distinctive and I think … because it’s just a lone figure in this nondescript background, it’s quite intense in a way. It’s just this incredible interaction that you have with a person. And yes, of course they are completely human, but there are also aspects about them that aren’t realist as well.

I did a lot of reading about Alphonse Bertillon, who was a police officer and criminologist in the late 1800s; he devised a system for measuring, he was into biometrics, which is the physical measuring of the body and faces and features and skulls and things. And he realised that there was no system to catalogue criminals, basically. So he would take measurements of the whole body, but specifically the skull. He would measure the bridge of the nose and the eyes and the ears, all around the skull and things, and then these became the forerunners of ID cards, mugshots basically, that police use today. And on these little cards would be all the details of tattoos or scarring, the colour of the eyes. And so this one card became a whole person’s identity, it described the person’s identity.

So I began to collect those. I saw a great exhibition at MoMA [NYC] of the very first ones of these—they’re very beautiful, it’s Victorian photography, but it was literally that isolated figure, and I began to make work from those, a good few years ago now, but that was the starting point of the isolated figure. I think I’m so drawn to that direct gaze, that it can make you feel incredibly uncomfortable, but it can also be that mirror into a person, when you look at the eyes and you can read so much about a person from that direct gaze, I think.

Yeah, definitely. I love the fact that you also blur gender boundaries as well, because you’re not even quite sure what you’re looking at it. It doesn’t necessarily matter at all, but I love the fact that it is just a person at the end of the day.

Yeah. Definitely the newer work has gone [in] that direction. I think, without being too prescriptive about it, I think it speaks of the times as well at the moment and that discussion that people are having. I mean, I’m so interested in that in-between, not knowing, not saying, not having to label, the openness really.

With the new works, what really draws you to a sitter because, unlike the Victorian photography, you’re now sourcing images from the internet and social media and places. I mean, what really draws you to someone you want to paint?

I was talking about this the other day and it is purely a gut reaction, I think. I think it is that I see somebody, see a thing in someone’s face, and I have an absolute instant gut reaction to the point where I just really want to paint this person.

I love that!

The people I’ve been looking at recently are wonderfully extraordinary and I’ve always been drawn into the idea of costume or clothes being a signifier of a person’s character, or they can be, so I’ve been looking at that. Instagram is such a great platform for that because people are just bombarding, they’re putting images of themselves out there all the time and so it’s easy to see. You can flick through hundreds of images, but then there is always something about a person’s face, usually to do with the eyes, that draws me in and I just have a real gut instinct that I really want to paint them.

Can you talk about where you source these images from? Where do you go to find these figures?

Oh, well gosh, I mean, sometimes they can be friends of my children or they can be students who I see on Instagram, and then, literally, you can connect people on Instagram, you can look at who’s taken the photograph and look at their posts and things.

Insight into lives.

It is! In the past I’ve worked with historical archives and you can dig deeper and deeper and deeper, all online, in the same way you can mine Instagram for these images, and for me it’s very interesting, because people are—I mean, I use Instagram purely for work, it’s a great tool for work for me, but a lot of people, they’re just constantly posting images of themselves on a particular day, feeling a particular way, in a particular mood. I feel like I can curate an archive, really, with what I’m seeing and you can choose bits and pieces and put them together and then the series is born from that.

That’s interesting that you draw from these images, because is it sometimes that you don’t necessarily know these people—and how is it, painting someone who you don’t know, from an image?

Yeah. I mean, I’m very solitary as a person and actually the idea of painting from life, having someone in my studio is actually fairly terrifying for me. [Laughs.] I’ve always wanted to be distanced, I’d be really bad, I think, at trying to talk and paint and things. So for me, there’s something very valuable about that distance, that I don’t know them particularly well, although I do always contact the person that I’m working from. So therefore, there is a slight conversation, a relationship is built up, especially if I worked from a subject more than once. For instance, I painted ‘Elliot’ about five or six times, I think, and so we send each other little messages. I’ve never actually met him, but I send messages and he’s pleased with what’s happening and things, and he likes being a muse from a distance. But that really works for me, that physical distance is quite important. Sometimes I look at the paintings, I think they’re about me as much as they are about the sitter as well. So I think it makes that easier in a way, maybe.

Do you want them to be recognisable?

It’s not the main driver. And I think that you would be able to recognise them from the photograph, but I do change things, I do react to things. For me it’s really interesting at the moment that the larger works, the economy that’s in the mark-making, is something that’s getting more of a feature... I’m interested in the idea of how little you can actually put into the work before you, as a person, start reading a face, if you know what I mean. How little information I need to give before you actually see something that maybe isn’t necessarily there. So I tend to work into the surface quite a lot and then find that I take a lot of it away again and it sort of remains, but I’ve taken a lot of it away. So it’s obviously very tonal, my work; it relies on tone a lot.

What I find really interesting with your work as well, the aspect I love, is the clothing, the accessorising. Because even though you don’t see the lower half of the body, you see the earrings or the glasses or something. It’s such an interesting way that, I don’t know, an accessory or an external feature of someone can change so much about their identity. It’s so beautiful. By adding in these kinds of contemporary, I guess, clothing features, do you want it to speak to a certain time?

I guess so. I mean, I think that’s partly the draw for me to make the works of the subject. I’ve always been fascinated by streets, fashion, culture—all of that stuff—music, has always been a big part of my life and I think I’m just drawn to people that are, I don’t know, flirting with ideas of gender. So Elliot will wear a big hat and in the paintings everyone assumes that it’s a woman. It’s very interesting how people read that. But I am becoming much more interested in making those details part of the painting, keeping them in and really working into them in a way that I might not have done so much in the past. But I’ve always loved costume.

I am interested in what it is that defines us and gives us our identity. In the past I’ve explored ideas around social history, ethnicity and immigration and now gender and sexuality. With the new work I am exploring the physical manifestation of the character of the subject.

"Not that anything will ever take away the experience of standing in front of a painting or a piece of work or sculpture ... but I do think people are having to look at ways of looking at work and imagining." - Sarah Ball

Do you think you’re seeing things differently at all in isolation, with yourself and in your work?

Yeah, I mean I think so. It’s tricky here because basically we live very rurally, so there’s certain aspects that just haven’t changed at all. [Laughs.] I am going back to the studio, I am being able to work, but I think there’s a spirit around, people seem to have the spirit of recognising that there are certain very good things that have come from having to cut back on our lives and our excesses, we can’t travel. I think maybe it’s making people think, and I think that’s definitely something that I would take on board very much and enjoy. I quite like that small, quiet way of living and that’s been amplified in a way I think.

Do you find that you’re listening to any specific music? Because what was interesting talking with [artist] Ella [Walker] was the fact that she’s at her parents’ house and she was revisiting all these books that she hadn’t seen in years. And I wondered if by spending more time at home you are picking things up or reading something or listening to something or, I don’t know, what you’re watching?

Yeah, I guess so. I mean, throughout my life I’ve read a trilogy of books by Edna O’Brien called, The Country Girls. And so I’ve been re-reading that, again, and for me what’s really interesting—it must be about ten years since I’ve read it last, it was banned when it first came out. So when I read it for the first time I was about 19, and it became a bit of a coming of age book for me. And I’ve read it, as I say, throughout my life a few times. And then the last time, reading it now, in the book, the mother of the daughter dies in a boating accident. And I’ve always read it as from the daughter’s point of view, and suddenly at my age now with a grown-up daughter, I’m identifying with the mother figure in it, which I just think is so interesting, how life changes you and then how you react to work or music or literature or whatever.

But I also find that in the studio—I wonder if it is because everything is very quiet—but when I get to the studio, I tend to put on some really loud music. So I listen to The Clash or The Cure, really loudly, just to get into the mood, and then I quieten down, I just need to break through some noise or something. So yeah, just things like that. But I think it’s a very thoughtful time for lots of us, isn’t it?

How do you think this will change people or change the art world? Do you think we’ll see any differences?

Well, I’m guessing that people are beginning to explore ways of seeing work virtually, I think that seems to be a big thing. As I say, I’ve got exhibitions coming up and I’ve been invited, actually during lockdown, to participate in a couple of exhibitions that are all going to be online. Not that anything will ever take away the experience of standing in front of a painting or a piece of work or sculpture, whatever, but I do think people are having to look at ways of looking at work and imagining, I think.

Yeah, I think it’s so interesting. I mean, how do you feel about people seeing your work online versus real life?

Well, I don’t know. It’s funny; I mean, the last show I had, which sold, I think very few people actually did come and see the work in the flesh. The people that bought it, I don’t think a lot of them did [see it in person] because we’re in St Ives and I think a lot of people bought online. I think for me, as long as there’s been an exhibition… I think it’s sad if a work is made and just sells straight away and it’s not been seen. I think that’s quite sad.

Yeah, just the fact that it is seen in some way… What I find amazing, because I did a little thing for Timothy Taylor [Hessel curated an online show for the gallery titled, ‘Dwelling is the Light’ in April 2020], and actually people all around the world could see it.

Yeah, it is amazing, and I think that that is such a plus point to this. It’s been like Instagram, really. And I do think that galleries are thinking about that a lot now.

Exactly. I hope that we get to do something in real life though one day.

Yeah, that would be great. It would be good.

Thank you so much. This was wonderful.

Yeah, I hope I haven’t waffled too much because I do tend to lose my thread.

Not at all. You are so concise and wonderful, thank you so much, absolutely.

Thanks Katy.

It was so lovely to speak to you as well and catch up.

Yeah, you take good care.

Related Articles

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews

Liberty 150 x150 curated by Leith Clark: The Founder Interviews